![]()

American Doctor Who fans befuddled by Capaldi’s accent: ‘He should be called Doctor What!?’

As the Glasgow-born star’s accent drives Americans to subtitles, we asked experts: is it the Scottish twang, or just his voice?

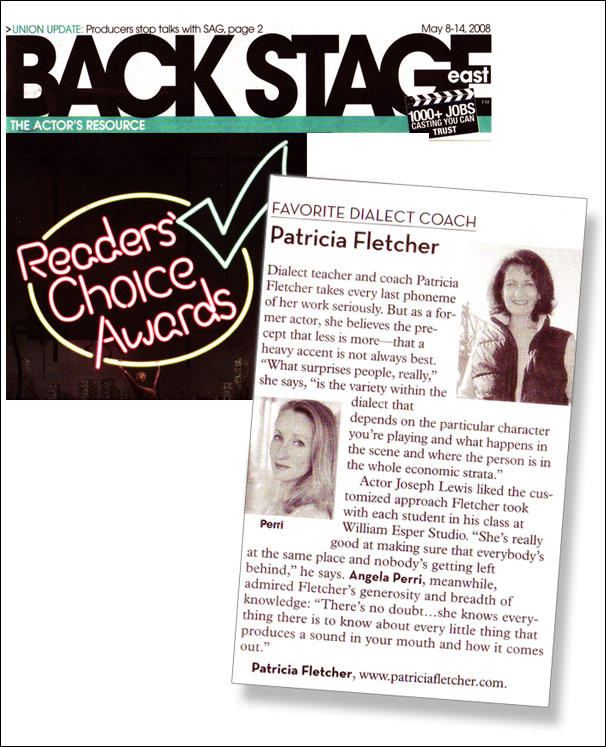

“…. I do not believe it is purely the accent that is throwing off the American audience,” said Patricia Fletcher, a Manhattan-based voice, speech and dialect coach who counts Harvey Keitel and Lynn Redgrave among her clients.

“The actor often speaks very quickly, with a staccato rhythm and without enough attention to articulating through to the end of his thought/line,” she added. “This does promote a character choice of Doctor Who being sharp and quick-thinking, but does not help us understand what the Doctor is actually saying/thinking. ….”

Original Article: http://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2014/sep/11/doctor-who-peter-capaldi-american-fans-scottish-accent?CMP=twt_gu

If These Knishes Could Talk Gabs About New Yawk Accents (VIDEO)

If These Knishes Could Talk Gabs About New Yawk Accents (VIDEO)

What exactly is a New York accent?

If These Knishes Could Talk is all about the way New Yorkers speak, and have spoken for decades.

Some in the film trace the accent back to the city’s working class roots — an amalgam of all the newly arrived immigrants in the early 1900’s. But some worry that New York’s accent is being washed away in a sea of gentrification as the city becomes prohibitively expensive for many natives.

For others, the accent is a curse — at least one woman in the film is actively trying to get rid of any vocal trace that she’s a New Yorker.

And she’s not alone. In November, the New York Times wrote a piece about longtime city residents seeking professional help to change the way they speak.

WATCH the trailer for If These Knishes Could Talk:

Original Article: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/04/14/if-these-knishes-could-ta_n_849110.html

A Dialect Coach Evaluates 3 Broadway Shows

A Dialect Coach Evaluates 3 Broadway Shows

MARK KENNEDY, Published: 4/25/2014

This theater image released by The O+M Company Jefferson Mays, center, during a performance of “A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder,” at the Walter Kerr Theatre in New York. (AP Photo/The O+M Company, Joan Marcus)

NEW YORK (AP) – That special sound you hear on Broadway these days could be a British accent.

Three hit shows – “Matilda the Musical,” ”A Gentleman’s Guide to Love & Murder” and “Kinky Boots” – all have mainly Yanks in their casts playing English men, women, boys and girls.

How are they doing? For the most part, not too bad, said Patricia Fletcher, a dialect coach for film, TV and stage actors who teaches at the New School for Drama and has seen all three shows.

“They all delivered in different ways,” said Fletcher, who has trained such actors as Harvey Keitel, Lynn Redgrave, Jean Reno, Drea de Matteo, Elias Koteas and Gina Gershon. “They really came through for the most part.”

The show that fared best in her book was “Gentleman’s Guide,” a show set in 1909 in England about an impoverished man who discovers he’s ninth in line to inherit a fortune, so he decides to eliminate the eight heirs of the D’Ysquith family standing in his way. All eight victims are played by Jefferson Mays – two women and six men.

“They really had character within dialect,” Fletcher said. “I don’t have that much real criticism, especially if I’m focusing on dialect. I think people are going to be entertained and have fun.”

The other two shows had some problems: “Kinky Boots,” the high-energy Cyndi Lauper musical about a British shoe factory that finds new life in drag footwear, had accents that were inconsistent, Fletcher found. But, she added, few may notice amid the cross-dressing, dancing and jokes: “It’s so wild that you almost expect the dialects to be just over the top anyway.”

The dialect in “Matilda,” a witty musical adaptation of the beloved novel by Roald Dahl about a telekinetic schoolgirl, was good, but it often got washed out by overlapping voices and complex choreography, she said.

“The best one technically was ‘Gentleman’s Guide,'” she said. “‘Kinky Boots’ was in and out. With ‘Matilda,’ I don’t think it was the dialect as much as the staging and the fact that they had everybody doing everything at once.”

A spokeswoman for “Matilda” declined to comment, saying the show speaks for itself. Rick Miramontez, a “Kinky Boots” representative, replied: “We think our American cast members do a fantastic job with their characters’ dialects. The characters’ genders, however, are indeed often inconsistent.”

Perhaps one of the reasons “Gentleman’s Guide” was tighter dialect-wise is that the show has an unofficial accent cop – Jane Carr, an English-born former member of the Royal Shakespeare Company who has been on the TV show “Dear John” and on Broadway in “The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby” and “Mary Poppins.”

Carr will diplomatically take aside an actor if he or she has made a mess of a pronunciation at least three times. “It’s not easy to be consistent in another accent, things do get stretched a little. I try to readjust it when it starts sounding wrong.”

Ultimately, Fletcher doesn’t think most Broadway audiences will much care about some poor pronunciations. The fact that all three are exuberant musicals and not serious dramas gives the actors plenty of leeway.

“If you’re not a dialect coach, you’re not going to be bothered that actors are dropping things a bit,” she said. But, Fletcher added with a laugh: “They wouldn’t get away with it in England.”

“How can I speak English well?”

The current White House Press Secretary flubs overs his words so dramatically and so often that GQ made Sean Spicer a special set of “Alternative ABCs.” So, suffice to say, the English language is complicated and daunting—even for the mouthpiece of the current presidential administration, whose sole responsibility is to explain the happenings of the government in a clear, coherent way.

What you are asking is a multi-layered question. Instead of making up your own words or alphabet, consider the options for growth at your disposal. Speaking English “well,” as voice, speech, dialect, and audition coach Patricia Fletcher explains, is entirely subjective.

“If other[s] are having a difficult time understanding you and that is troubling you, you might consider taking an accent reduction or neutralization class or studying privately with a teacher [or] coach,” Fletcher suggests. She also recommends Skype coaching sessions, although she says they aren’t as effective as in-person sessions.

The School of Languages, housed within The New School for Public Engagement on the sixth floor of the 66 West 12th Street building, offers language programs and English as a Second/Foreign Language (ESL) certificate-granting courses for individuals interested in improving their grammar, academic writing, listening and speaking, and reading capabilities in English.

Fletcher, who has taught at The New School for Drama, along with other college acting programs in and around Manhattan, strongly suggests taking an English grammar class either at The New School, a different New York City language school, or online. English Grammar 101 offers free modules and online quizzes that extensively outline nouns, punctuation, verbs and phrases, and other fundamental aspects of grammar comprehension.

“There are many available sources on YouTube that might be useful,” Fletcher says.

But, if by “speaking English well,” Fletcher says, “you mean that your knowledge of particular English words is not what it could be,” taking a class might be unnecessary. Devouring books like Word Power Made Easy: The Complete Handbook for Building a Superior Vocabulary by Norman Lewis (available on Amazon for under seven dollars) could help your vocabulary flourish.

“There are several phone apps now available for all of the above: English grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation,” Fletcher adds. One example of such is Duolingo, a free gamified learning application that teaches a variety of languages, including English, through quick, effective, and engaging lessons. “So, there are lots of options, many free or low cost, which are available if you wish to continue your English studies.”

Of course, if these suggestions seem too overwhelming, you can always embody Sean Spicer, and creatively create your own unique vernacular.

Read Full Article From Cosmo Magazine

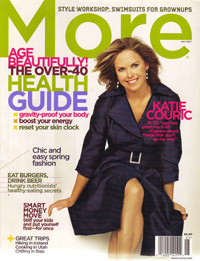

THE SOUND OF EXPERIENCE

BY AMANDA ROBB

MORE Magazine

MAY 2007

The day of my fortieth birthday began the way many of my days do: on the phone, conducting an interview. This particular someone was a textile maven who was enlightening me on the hallmarks of first-rate camel hair. I’d thoroughly prepared for the interview and was, if I do say so myself, prompting him with well-researched, insightful questions. Midway through a detailed explanation of the molting habits of Bactrian camels, the expert stopped short to ask, “Sweetie, are you sure you’re following me?”

The day of my fortieth birthday began the way many of my days do: on the phone, conducting an interview. This particular someone was a textile maven who was enlightening me on the hallmarks of first-rate camel hair. I’d thoroughly prepared for the interview and was, if I do say so myself, prompting him with well-researched, insightful questions. Midway through a detailed explanation of the molting habits of Bactrian camels, the expert stopped short to ask, “Sweetie, are you sure you’re following me?”

I wanted to say, “We’re talking about shedding animals, not neuroscience, and yes, somehow—maybe thanks to my 10 years’ experience as a journalist, or my graduate education, or just by dint of four decades on the planet as a sentient being—I am keeping up.” But I held my tongue. Not out of professionalism or politeness, but because I knew in my heart that he was a genuinely concerned windbag. How? Because I’d say, conservatively, that about 70 percent of my phone acquaintances assume I’m an idiot.

Why? Because as every other part of me has ripened and matured, my voice has remained defiantly young. Truly, from my accomplished mind and vigorously maintained body comes forth a nasal, insecure Valley girl who, at least once during her every conversation lasting more than five minutes, is asked to repeat herself because not only does her voice have Peter Pan syndrome, she mumbles, to boot.

I despaired. But as promised in The Sound of Music, when God closes a door, somewhere He opens a window. Lousy interview plus my birthday equals huge gift to self. And what was my heart’s desire? A new voice. A mature, smart-sounding, intensely appealing one with which to share my bits of brilliance with the world.

In less than an hour on the Internet, I found the Voice and Speech Trainers Association. The group’s mission is to “practice and encourage the highest standards of voice and speech use and artistry in all professional arenas.” There were about 30 voice trainers in my area. Most had résumés that boasted training such as Associate in Fitzmaurice Voicework, Estill Voice Craft Level 1, and 5 Rhythms Mysterium Workshop. I chose Patricia Fletcher because she had a master’s degree in voice and speech, and I understood what a master’s degree was. On the phone, she had just the kind of voice I wanted. Superaticulate, but not elitist sounding. Confident, but not strident. Absolutely female, but not flirtatious or fawning. Still, before signing up for the lessons, I quizzed her on what actually makes a voice sound gown-up.

Pat suggested I think about voices on sitcoms—voices intended to be silly or stupid. If you say ow! With a mature voice, the sound suggests that the speaker is hurt, she explained. But if you say it in a sitcom way—“smile and make it really bright and put the sound into the front of the face—ow! sounds funny. “So going up in pitch, being nasal, strident and thin, all of that makes the speaker seem not as powerful, not as grounded, not as experienced…maybe someone who wants to please a little too much.” Another authority sapper, she said, “is being breathy.” Pat did a killer Marilyn Monroe impersonation by saying with a sigh, “This makes me sound uncertain, a little weak.”

I asked to start classes the next day.

It turned out that I vaguely remembered Pat from her 1980’s role as a housekeeper on the ABC soap opera All My Children. And I was still feeling a little starstruck when she flipped on a tape recorder and asked me to recite “Humpty Dumpty”.

As a character in the musical A Chorus Line sings,” I dug right down to the bottom of my soul…”

“You breathe in a very high way, from your collarbone,” Pat said. “And you have back-of-the-throat and tongue tension that makes your sound escape out your nose more than it needs to.”

“Curable?” I asked.

She instructed me to just breathe for a few minutes. With her watching so intently, exchanging oxygen form carbon monoxide seemed an extremely complex, rather than an involuntary, task.

“Dancer?” she asked.

I beamed. “Ballet three times a week!”

She groaned and told me that good dance posture is terrible speaking posture. Holding your abdominal muscles right and high, for example, prevents the breath from dropping into the bottom of your lungs, which is basically your belly, which you need to keep soft so it can fill up with air.

It was my turn to groan. My rock-hard tummy (with a wee bit of padding since I had the baby, um, seven years ago) was my pride and joy.

“Look, I’m not asking you to get fat,” Pat said as I hemmed and hawed and edged toward her door, “just to relax your abs.”

Only because she’s much thinner than me, I decided to attempt a few of her exercises, the first of which require positions that bring to mind things that don’t, per se, involve the voice.

In the first one, we lie down on Pat’s floor with our legs up on her sofa. The idea was that by securing the pelvis and shoulders, the belly would be the only thing that could move as we breathed in, saying k-ah. On my inhale, lo and behold, my rib cage blew up in a way I thought it only could during pregnancy. To my enormous relief, on the h-ah exhale, my frame entirely recovered its dainty proportions. When I accomplished this several times, Pat announced it was time to “F” Humpty Dumpty.

I was deeply intrigued.

Note of candor: It wasn’t that great.

Note of caution: If you try this at home, definitely do it lying down. You will get dizzy. What the exercise involves is making a series of F sounds to the beat of “Humpty Dumpty,” with no more than three syllables per breath. By the time the old egg is sitting on his wall, you get the point that you want to breathe deeply to talk.

Pat declared that I was ready to stand up. I practiced breathing while looking in a mirror to make sure that all my relaxing was not making me slouch. “We don’t want to be collapsing on ourselves to get the breath to release,” she said. My homework was to keep a hand on my middle as much as possible to make sure my rips were expanding every single day, all day long.

My husband said that my walking around holding my ribs made me look as if I were always about to yell at him, but that he was willing to put up with it if it meant I’d be audible for the last half of our lives.

“Thanks,” I said, extremely audibly.

My next nine sessions with Pat were devoted to relaxing my jaw, throat and tongue, which were a shockingly uptight trio. I never actually mastered “jaw shakes,” but I either stopped clenching enough or got frustrated enough that Pat let me move on to stretching out the tongue, which had been shamelessly lounging in the wrong place in my mouth. Your tongue is supposed to rest low in your mouth with the tip behind your lower teeth. My tongue sat up very high, sending a lot of sounds out my nose. But the only sounds in English that are supposed to come out of your nose are m, n and ng.

Trust me, it is harder to train a tongue than it is to train a puppy. The thing just goes where it wants to go. Pat’s exercise for this one was basically tongue stretches, done by saying k-ay and remembering that your tongue is a muscle that extends all the way down your throat. And it really is a muscle: When I left Pat after the tongue sessions, my lingua was licked.

Finally, it was time to get to what I thought we’d start with: enunciation. I told Pat that I’d like to speak like Katharine Hepburn in Bringing Up Baby or Alan Rickman in any performance. Pat frowned, then said either dialect would be pretentious for a 40-year-old woman raised in Reno, Nevada. She suggested we work on well-pronounced neutral American speech.

“Who talks like that?” I asked.

“Jim Lehrer,” she said, “on the PBS News Hour.”

But although I had long harbored a mad crush on Jim Lehrer, I didn’t aspire to speak like him. That night I asked my husband, “Wouldn’t it be exciting to be married to someone who speaks like Katherine Hepburn or Alan Rickman?”

He said that really he just wants to be married to someone he can understand and that under no circumstances did he want to be married to someone who sounds like Alan Rickman and really sometimes I am so strange he thinks I’m making him lose his hair.

Gee, I wanted to save the Sturm and Drang for bigger fish. I accepted neutral American speech as my dialect goat. Pat tried, with great patience, to teach me how to say sounds correctly. “Vowel sounds must be open,” Pat said, “with your vocal cords nice and wide.” She opened her mouth wide enough to put my head in it.

Show-off, I thought.

“If the vocal cords half come together and half release, you’ll get a sound that’s sort of scraping. And that’s a young, not-serious sound that I hear from women much more than men,” she admonished.

I repeat about a million phrases, such as “step in,” “paint it” and “pick actors.” Pat was very hard to please, and I swear to God my tongue cramped. If it could have, it would limped right out of my mouth. After three sessions, I moved up to sentences, such as “Can you explain why you refused to reply?” I start over-enunciating. Pat reminded me that “English. Is. Not. Spoken. As. If. A. Robot. Is. Talking. As in French, our words blend together. The important thing is to say them clearly, with breath support and the tongue in the correct place, and to finish saying them.”

“I understand,” I told her. “Really, I do. Everything you’ve taught me is firmly rooted in my gray matter. But sometimes it feels as if you’ve taught me the mechanics of a triple salchow. As well as I understand it, I’m never going to speed along ice, leap off one blade, turn three times in the air and land on the other. Sorry.”

“You said that beautifully,” Pat said. I swear she had tears in her eyes. “Gorgeous breath support, deep intonation, clear articulation. Even intentionality.”

I beg to graduate. Pat says, “OK.”

I know that I have not become anything close to a perfect neutral American speech speaker. But I have made progress. If I do my exercises, if I think hard before speaking, my interviewees don’t lose their train of thought for fear I’m barely post-adolescent. But the second my well worked-out speaking apparatus slips my sometimes bushed brain’s attention, it’s “sweetie” all over again.

AMANDA ROBB IS A NEW CITY-BASED FREELANCE WRITER.